My whole life, I have watched on-screen versions of Charles Dickens’ classic tale A Christmas Carol starring the world’s most wretched miser, Ebenezer Scrooge, and the impoverished yet humble Bob Cratchit and his family. I must have watched a dozen or more renditions from the 1951 version featuring Alastair Sim to Scrooge McDuck and Money in 1967 to Jim Carrey’s 2009 version to the darker and more adult 2019 A Christmas Carol mini-series starring Guy Pearce. Until this year, however, I had never actually read the novella.

I decided to read A Christmas Carol from beginning to end to my English classes at school. That necessitated that I read and analyze it myself beforehand. I have now read A Christmas Carol five times and I’m struck by how emotional, insightful, uplifting, powerful, and poignant it is. The book caused me serious introspection and brought me to tears, I’m not ashamed to admit it, more than once.

For those unfamiliar with the story, here are the five story elements of A Christmas Carol:

- Characters: The primary character is the rich but misanthropic moneylender Ebenezer Scrooge. His former business partner Jacob Marley, now a ghost, plays a key role. The three other specters – the Ghost of Christmas Past, the Ghost of Christmas Present, and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come – are critical to the story. Scrooge’s Nephew is a tertiary character whose role should not be overlooked. And, of course, we have Bob Cratchit, Scrooge’s penniless assistant, and his struggling family.

- Setting: Written in 1843, the book depicts London ravaged by the industrial revolution with its extreme disparity between rich and poor.

- Plot: The story revolves around Scrooge’s hardened heart and how it may be softened through the influence of spirits who transport him to his past, who show him his influence on others at the present time, and who display the bleak future he may face if he continues along his path of stinginess, selfishness, and seclusion.

- Conflict: The major problem of the story is Scrooge’s hatred for mankind, his obsession with money, and his caustic attitude towards everything and everyone. It is an internal problem; a conflict of the soul that must be resolved in the not-so-silent chambers of Scrooge’s black soul.

- Theme: The overarching themes of this story are the emptiness of avarice, the sin of selfishness, the true meaning of Christmas and being a good human, and the merciful hope of redemption held out to even the worst of humanity.

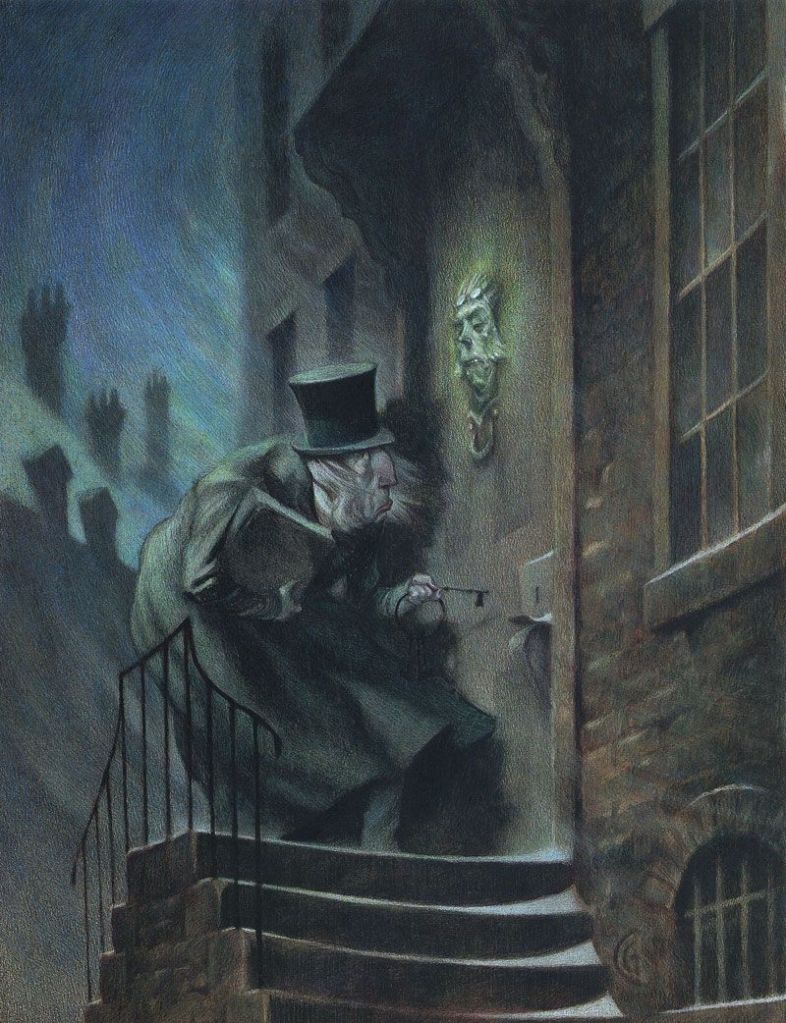

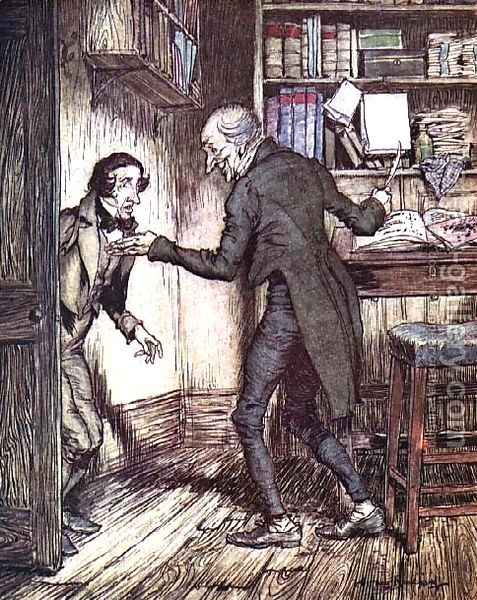

The book opens with Ebenezer Scrooge being the foulest, stingiest, most contemptible misanthrope in the world. His wretchedness is marvelously described in these words:

“Oh! but he was a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster. The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice. A frosty rime was on his head, and on his eyebrows, and his wiry chin. He carried his own low temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dog-days, and didn’t thaw it one degree at Christmas.

“External heat and cold had little influence on Scrooge. No warmth could warm, no wintry weather chill him. No wind that blew was bitterer than he, no falling snow was more intent upon its purpose, no pelting rain less open to entreaty. Foul weather didn’t know where to have him. The heaviest rain, and snow, and hail, and sleet could boast of the advantage over him in only one respect. They often ‘came down’ handsomely, and Scrooge never did.”

From this description, we see that Scrooge is coldhearted, hardened, surly, covetous, stingy, reclusive, and self-absorbed. We later learn that everyone, including dogs, avoids him and he likes it that way. He carried the cold around with him and the climate at the beginning of the book was described, fittingly, as dark. In a word, Scrooge is the quintessential miser.

Furthermore, Scrooge spends his entire life lending, counting, collecting, and coveting money. He sees everything in terms of monetary value and has no compassion for anything not worth its weight in gold, even causing the breakup of his long-term engagement because of his obsession with wealth. He has no respect for those who lack money, seeing them as “idle” and deserving of their plight. He is the last person someone should ask for donations to the poor.

Early in the story, two “portly gentlemen” arrive at Scrooge’s counting-house to ask for Christmas donations for the needy. Scrooge’s replies astonish them and drive them away. When told of the thousands upon thousands who needed extra support, Scrooge asked, “Are there no prisons? . . . . And the Union workhouses? Are they still in operation? . . . . The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?”

To Scrooge, the poor were layabouts who ought to go to prison, the inhuman workhouses, or be sent to work on the treadmill – a medieval type of device exactly like, though larger than, our modern treadmill that was invented to keep prisoners busy and to generate energy for local businesses.

The gentlemen were naturally appalled at the suggestion and said that some people would rather die than go to the infamous workhouses. Even more appalling than the idea of sending the “idle” poor to prison or to hard labor, was Scrooge’s response to people preferring death to subhuman living standards. He quipped: “If they would rather die, they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

Scrooge was no kinder to his own nephew who visited him to invite him to Christmas dinner the following evening. To his nephew Fred’s well-wishes, Scrooge responded with his infamous, “Bah! Humbug!” Humbug is a word that expresses the idea that he doesn’t believe the sincerity of those who wish anyone a “Merry Christmas!” He believes it is all pretense, hypocrisy, and lies. The entire holiday was, to Scrooge, utter nonsense.

Scrooge showed his Marxian, materialistic logic when he demanded of his nephew:

“What right have you to be merry? What reason have you to be merry? You’re poor enough.”

Fred’s response is one of the most piercing in the novella:

“Come, then. What right have you to be dismal? What reason have you to be morose? You’re rich enough.”

Not even Scrooge had an answer to this flash of truth. At the beginning of the story, Scrooge knew nothing but dollars and cents (or farthings and sixpence). Nothing else mattered. And people mattered to him a great deal less than his stash of gold. Scrooge did not even care about himself, depriving himself of warm fires, good food, and light just to save a few coins.

Later, a boy came to Scrooge’s office door to sing Christmas carols. He barely got out “God rest you, merry gentlemen” when Scrooge frightened him off. There was no song in his heart – especially not on Christmas.

At the end of the workday, Scrooge begrudgingly granted his assistant, Bob Cratchit, whom he had previously threatened with firing when he spontaneously applauded something Scrooge’s nephew said, the full day off on Christmas. As he did so, however, Scrooge called it, “A poor excuse for picking a man’s pocket every twenty-fifth of December!”

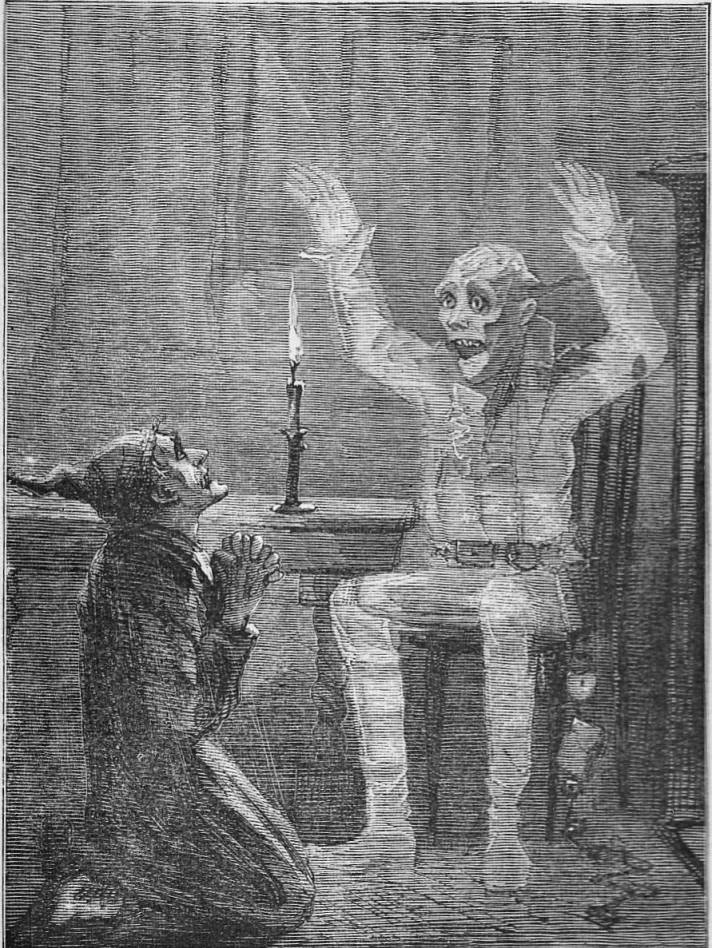

Having established Scrooge as the most miserly wretch imaginable – the most insufferably arrogant and greedy curmudgeon you have ever had the misfortune of encountering – the story began in earnest with the appearance of the first ghost, Scrooge’s departed business partner Jacob Marley.

At first, Scrooge doubted Marley’s existence, saying that it was all a figment of his imagination likely caused by “an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato.” In short, Scrooge concluded, with an uncharacteristic bit of humor: “There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

Marley would have none of it because he knew how deadly serious Scrooge’s situation was. He let out a “frightful cry, and shook its chain with such a dismal and appalling noise” that Scrooge nearly fainted. By terrifying him nearly to the point of unconsciousness, Marley convinced his old partner that he was indeed real.

Having established the fact of his sad existence, Marley warned Scrooge that his fate would be more severe than even Marley’s if he did not alter his present course. Scrooge observed that Marley was bound in a highly symbolic chain comprised of “cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel.” Marley told Scrooge that his own chain was already that long seven years previous, that he had “laboured on it since,” and that it was a “ponderous chain.”

Marley taught Scrooge that it was a living hell “to know that no space of regret can make amends for one life’s opportunities misused!” But, countered Scrooge, his mind on money as always, Marley had been a good businessman. At the thought, Marley was stricken and uttered the famous words:

“Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business ; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

He then wrung his chains and was needled by his “unavailing grief,” intensifying Scrooge’s rising fear. Despite all this, Marley held out the chance of redemption to his miserly partner. The only chance was for Scrooge to be haunted by three additional spirits. Scrooge declined. Marley, caring more for his immortal soul than Scrooge evidently did, replied: “Without their visits, you cannot hope to shun the path I tread.”

Marley then departed, showing Scrooge a street full of similarly bound and moaning spirits wandering about in “restless haste.” We are given to understand that their wailing and sorrow was a result of their extreme regret and the acknowledgement that they wasted their lives pursing the things, like wealth, that were of no eternal value: “The misery with them all was clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.”

Though he preferred not to be haunted, Scrooge was indeed haunted by three spirits that the same night – Christmas Eve. The first was the Ghost of Christmas Past. His appearance was peculiar, but the most interesting and symbolic part of him was that a jet of light emanated from his head, perhaps symbolizing the light of truth and the terrible knowledge reality gives.

This spirit first showed Scrooge his lonely, depressed, neglected self at boarding school one Christmas. He had been abandoned by his classmates and by his family. His only friends were imaginary characters in books. Scrooge “wept to see his poor forgotten self as he had used to be.” He pitied himself, exclaiming “Poor boy!” more than once. As he watched himself and observed this lonely little boy, every sound and sight “fell upon the heart of Scrooge with softening influence, and gave a freer passage to his tears.”

Something else happened, too, that hinted at this same softening. Scrooge suddenly remembered the boy singing Christmas carols whom he had frightened off. Prodded by the spirit, he said he wished he could have given the boy something, but said finally, “it’s too late now.” The spirit “smiled thoughtfully and then showed Scrooge his sister Fan who came to take him away permanently from the boarding school on a later Christmas.

Fan divulged an important detail about Scrooge’s upbringing when she said: “Father is so much kinder than he used to be, that home’s like heaven!” While we don’t know precisely what Scrooge’s father had been like, we know he could not have been a positive influence on the boy. Was he abusive? We don’t know. Was he bad-tempered? That seems certain. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. Perhaps, though it is conjecture, older Scrooge recognized that he had become like his father.

What we do know is that Scrooge dearly loved his sister and that she died fairly young. The following conversation stands out:

“She died a woman,” said the Ghost, “and had, as I think, children.”

“One child,” Scrooge returned.

“True,” said the Ghost. “Your nephew!”

“Scrooge seemed uneasy in his mind, and answered briefly, “Yes.””

It seems that Scrooge was instantly reminded of his conversation earlier that day with his nephew where he had pronounced Christmas a “humbug!” and had rudely declined his invitation to come to Christmas dinner. In doing so, he dishonored his beloved sister Fan and proved himself to be a man very different than he once was, a man like his father, a man hardened with time.

The Ghost of Christmas Past next showed Scrooge his former master under whom he apprenticed, Mr. Fezziwig. Fezziwig as a jovial man who loved Christmas, loved people, and loved his employees. He threw a grand party where, in spite of himself, older Scrooge found himself dancing along to the music and reveling in the memory.

The spirit then caught Scrooge in his own hypocrisy when he showed him his former self singing Fezziwig’s praises over something so trivial as a party. Scrooge, enmeshed in the memory of old Fezziwig, defended his master against the Ghost saying that it was really a “small” thing Fezziwig had done in throwing the party and was not worthy of so much praise. Without thinking, Scrooge said that it wasn’t the money or the party that mattered, but, rather, that:

“He has the power to render us happy or unhappy; to make our service light or burdensome; a pleasure or a toil. Say that his power lies in words and looks; in things so slight and insignificant that it is impossible to add and count ‘em up: what then? The happiness he gives is quite as great as if it cost a fortune.”

At this, Scrooge recognized his own faults and how very unlike Fezziwig he was with his own apprentice, Bob Cratchit. He then sheepishly admitted that he “should like to be able to say a word or two to my clerk just now” – a clerk he had accused of robbing him by wishing Christmas to spend with his family.

Scrooge was beginning to reel under the weight of his own hypocrisy, but the spirit had another gut punch planned for him. As we have seen, though he came from a neglected and troubled childhood and grew up with an ill-tempered father, he was not always the miser he became. In fact, he even had a heart that could enjoy Christmas and that could love. Scrooge was engaged to a girl named Belle; a name, I’m sure, chosen for its symbolic meaning, “Beauty.”

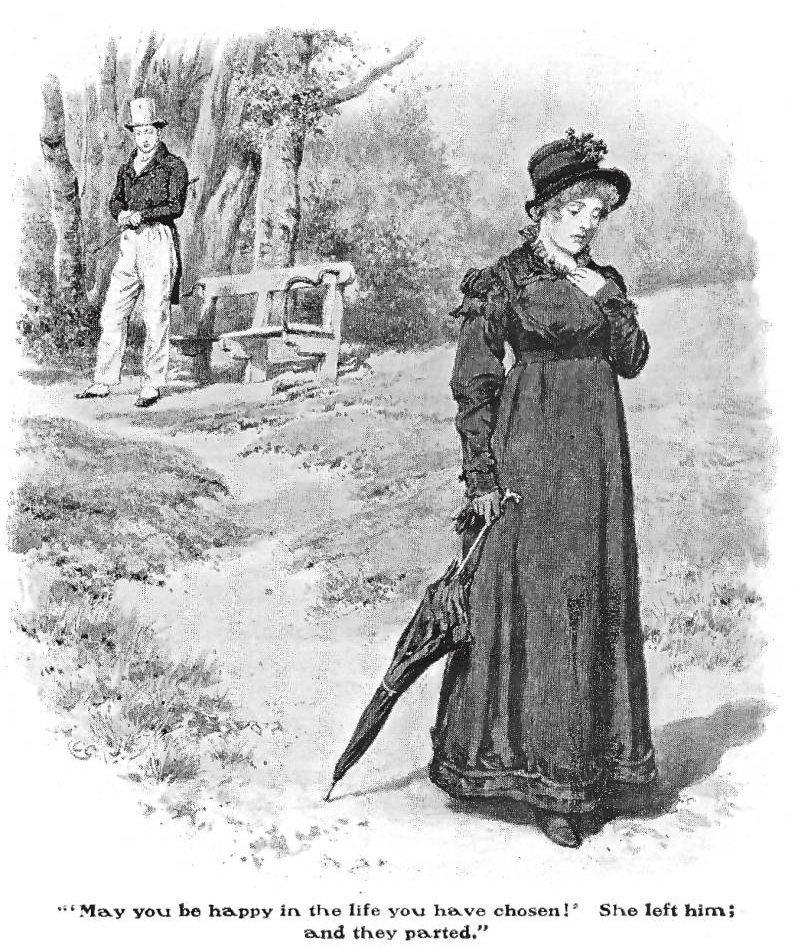

When we first see Belle, on a Christmas long ago, she was in mourning and was in the process of breaking up with Scrooge. Scrooge seemed not to understand why she was leaving him. She explained: “I have seen your nobler aspirations fall off one by one, until the master passion, Gain, engrosses you.” Former Scrooge brushed off the remark claiming that he had simply become “wiser” and that he had matured into a man. Yet, Belle said that Scrooge had de facto ended their relationship. “How?” he demanded. Her reply:

“In a changed nature; in an altered spirit; in another atmosphere of life; another Hope as its great end. In everything that made my love of any worth or value in your sight.”

She then asked him a question that cut through his pretenses: “If this had never been between us, tell me, would you seek me out and try to win me now? Ah, no!”

Had they never met before Scrooge grew to love money beyond all else, he would not have given a poor girl like Belle a second thought, and he knew it and knew that Belle knew it. Thus, the engagement ended with Belle wishing him happiness in the life he had chosen.

Older Scrooge, no matter how much he might have protested it, knew the truth that there had been no happiness in his life. Contrasted with the life he once had, his present life was misery. Scrooge, in pain, demanded:

“Spirit! show me no more! Conduct me home. Why do you delight to torture me?”

When the Ghost of Christmas Past told him he had one more “shadow” to show him, Scrooge cried out: “No more! No more! I don’t wish to see it. Show me no more!” The truth was too much for him; too painful; too real. Nothing is more painful than for a guilty man to be confronted with the truth of his wicked ways and to realize that life could have been otherwise had he so chosen.

Nevertheless, the spirit showed him one more memory. It was not his memory, but it an event of the not-too-distant past showing him exactly the joy he missed out on – the joy he passed up by choosing money over love.

The scene is precious – excited children making playful havoc in a humble home with their mother on Christmas Eve. Their mother was, of course, Belle. She was happy; truly happy. Her husband then arrived home with Christmas presents for the young ones. When the festivities died down and Belle, her husband, and one of their daughters was left, Scrooge imagined for a fleeting moment a little girl calling him father. Then Belle’s husband mentioned that he had seen Scrooge earlier that day, alone in his office and “quite alone in the world.”

At this point, Scrooge’s regret was too strong and he could handle no more. We read this exchange:

““Spirit!” said Scrooge in a broken voice, “remove me from this place.”

““I told you these were shadows of the things that have been,” said the Ghost. “That they are what they are do not blame me!”

““Remove me!” Scrooge exclaimed, “I cannot bear it!” . . . .

““Leave me! Take me back. Haunt me no longer!”

Then Scrooge remembered the light coming from the ghost’s head and associated the light with his present pain. He grabbed the ghost’s cap and pushed it down over his head to extinguish the light – to cover his past sins from his eyes. Haven’t we all experienced the same pangs of regret from our choices and the corresponding urge to run, hide, or extinguish the awful truth about ourselves?

Scrooge was subsequently haunted by the Ghost of Christmas Present. He saw into Bob Cratchit’s life of abject poverty and how he and his family were nevertheless happy. He saw that Bob Cratchit’s crippled son, Tiny Tim, would die unless the family received assistance. He saw the joy and Christmas cheer experienced by humble miners, men in lighthouses and on ships, and the poor. He saw his nephew’s Christmas party, the very one he had rejected an invitation to and how glorious it was. The music at that party reminded him of his sister and of all the things the Ghost of Christmas Past had shown him. Under those memories, “he softened more and more.”

By the time the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come arrived, Scrooge had experienced a change of heart. He told the scary spirit who was clothed in black, had a face hidden in robes, communicated by pointing a spectral hand, and floated ominously, that “as I know your purpose is to do me good, and as I hope to have to be another man from what I was, I am prepared to bear your company, and do it with a thankful heart.”

Scrooge was shown that Tiny Tim, just before Christmas, had died. He saw how shaken up his family was, especially “little Bob” Cratchit, his father. He lost the spring in his step and walked slower because his precious little child had gone. His older brother, Peter, was found reading the words, “And he took a child, and set him in the midst of them.” Scrooge wondered where he had heard those words before, a subtle hint that he had not read his Bible in quite some time.

The words come from Mark chapter 9, verse 36. The full passage, whose relevance to Tiny Tim’s death is no doubt apparent, reads:

“And [Jesus] sat down, and called the twelve, and saith unto them, If any man desire to be first, the same shall be last of all, and servant of all.

“And he took a child, and set him in the midst of them: and when he had taken him in his arms, he said unto them,

“Whosoever shall receive one of such children in my name, receiveth me: and whosoever shall receive me, receiveth not me, but him that sent me” (Mark 9:35-37).

Scrooge was also shown groups of people talking about some man who had died – a miserable man whom no one loved and who had no one to care for his corpse. One man commented that the Devil had finally claimed him. They made light of his death and wondered only what was to become of his fortune. Another group of people among the dregs of the city had robbed the man’s corpse, literally taking his bed-curtains down while he lay there and stealing the blanket from off the corpse. The only people moved with emotion at the news of the man’s death was a couple who owed him a debt. He had refused to delay their payment, which would lead to their total ruin. They were, therefore, filled with pleasure and thankfulness to hear he had died.

Scrooge did not put two and two together. He did not realize that the man whom everyone despised, robbed, and were glad he was dead was himself. He only learned the truth when the spirit showed him a tombstone chocked with weeds that read “Ebenezer Scrooge.”

Scrooge fell to his knees and pleaded:

“Spirit! Hear me! I am not the man I was. I will not be the man I must have been but for this intercourse. Why show me this, if I am past all hope? . . . . Assure me that I yet may change these shadows you have shown me by an altered life? . . . . I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach. Oh, tell me I may sponge away the writing on this stone!”

With that, Scrooge found himself in bed, face wet with tears. The nightmare was over; the morning had dawned. The darkness of the night had been replaced by the brightness of the day. Scrooge recognized he had been spared, and happily thought: “Best and happiest of all, the Time before him was his own, to make amends in!”

Scrooge again fell to his knees and pledged with his whole soul:

“I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future! The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. O Jacob Marley! Heaven and the Christmas Time be praised for this! I say it on my knees, old Jacob; on my knees!”

Scrooge was as good as his word. He cheerfully wished the world a “Merry Christmas!”, danced while he shaved, “frisked” around the house like a little boy, laughed and chuckled like he had not done in years, and reveled in the sound of church bells ringing. I’ll let Scrooge tell it:

“I am as light as a feather, I am as happy as an angel, I am as merry as a schoolboy, I am as giddy as a drunken man. A merry Christmas to everybody! A happy New Year to all the world! Hallo here! Whoop! Hallo!”

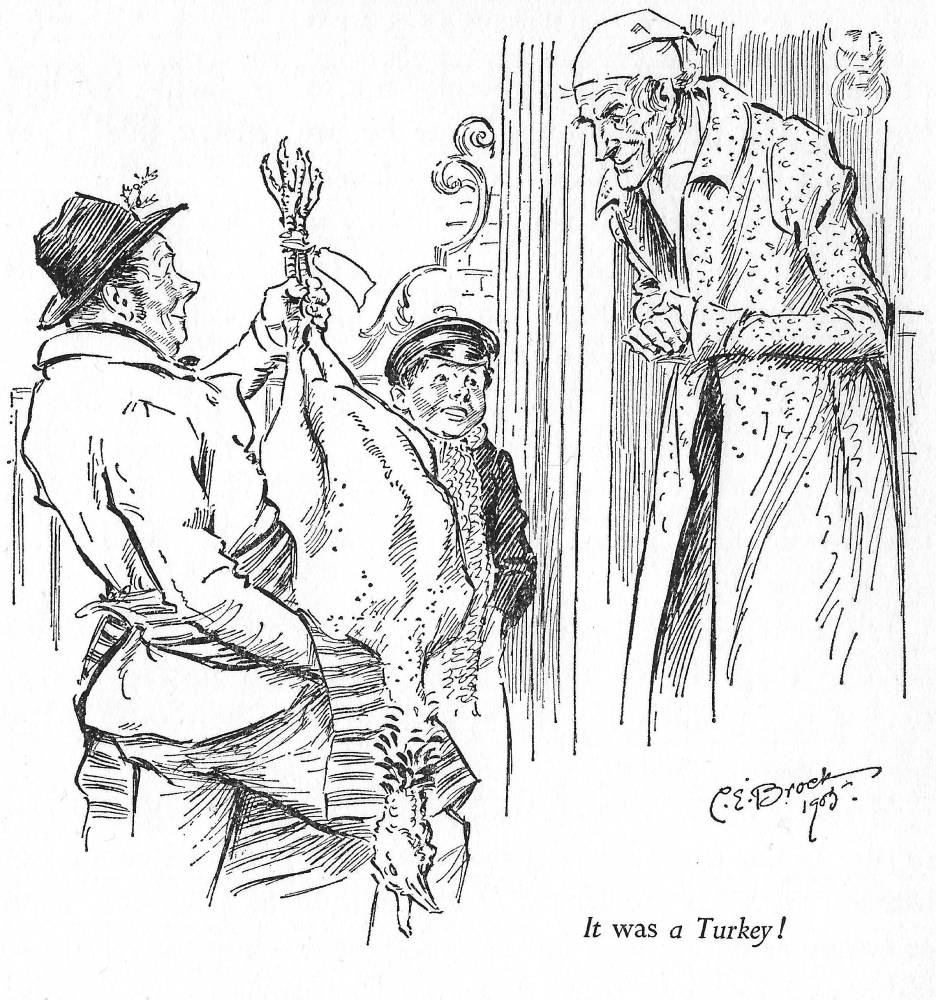

So, Scrooge anonymously bought the largest turkey he could and sent it to the Cratchits, dressed himself up nicely, walked the streets in an “irresistibly pleasant” mood, helped every beggar he saw, smiled delightfully, bumped into one of the portly gentlemen he had previously spurned and pledged an enormous sum to help the poor, and even went to church. When evening came, Scrooge overcame his shame and visited his nephew for dinner. His nephew, the sort who believes in humanity, welcomed him warmly and made him feel right at home.

The next day, Scrooge beat Bob Cratchit to the office, put on an air of anger that Bob was 18 minutes late, and then sprung the news upon him that he was going to raise his salary. Cratchit’s first reaction was to call for help so that a straitjacket could be placed on Scrooge who, it appeared, had obviously gone berserk. Scrooge exclaimed:

“A merry Christmas, Bob! A merrier Christmas, Bob, my good fellow, than I have given you for many a year! I’ll raise your salary, and endeavour to assist your struggling family, and we will discuss your affairs this very afternoon, over a Christmas bowl of smoking bishop, Bob! Make up the fires and buy another coal-scuttle before you dot another i, Bob Cratchit!”

Scrooge’s conversion was more than just in words. We read that he became everything he said he would:

“Scrooge was better than his word. He did it all, and infinitely more; and to Tiny Tim, who did NOT die, he was a second father. He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man as the good old City knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough in the good old world. Some people laughed to see the alteration in him, but he let them laugh, and little heeded them; for he was wise enough to know that nothing ever happened on this globe, for good, at which some people did not have their fill of laughter in the outset; and knowing that such as these would be blind anyway, he thought it quite as well that they should wrinkle up their eyes in grins as have the malady in less attractive forms. His own heart laughed, and that was quite enough for him.”

Therein lies the sure proof of his conversion, that he, like the Master, “went about doing good” (Acts 10:38). Scrooge became not only a great man in the eyes of the world that values, as he once did, money above all else, but a good man who helped the poor, relieved burdens, performed acts of kindness, smiled, laughed, and loved.

That is the message of A Christmas Carol. It is a hopeful message; a message of redemption. It shows us that no matter how lost we are, we might change; no matter how encrusted with the cares and sorrows and regrets of this life our hearts are, they can soften; no matter how surly and miserly we may be, we can smile and sing yet again. It shows us, in a word, the misery we consign ourselves to if we misprioritize what is important in life and the resplendent joy we may experience if we choose a life of service, goodness, and love.

For me, reading A Christmas Carol was a deeply emotional experience. It was emotional because I could see myself in Scrooge in more ways than one. If you cannot see yourself in Scrooge, I sincerely commend you. But I think the story was written so that you could see yourself in him. It is not a pleasant thing to see yourself in someone described as a “squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner,” yet, just as Scrooge discovered, it is better – even if more painful – to face the light of truth than to hide it.

Following Scrooge on his journey through his past caused me to reflect on my own past. As Scrooge confronted his regrets and failings, I confronted mine. And as Scrooge couldn’t bear it, it was hard for me to get through, too. As Scrooge wept, so did I. Yes, so did I.

I don’t often talk about my personal regrets, failings, and sorrows publicly, and I won’t today, but they are real, and they hurt. Some are self-inflicted wounds and others are not. In some ways, I have reacted to these injuries in the same way Scrooge did, by becoming harder, colder, and more cynical about the world. That is a truth that hurts to face and a bitter pill to swallow.

It is significant, therefore, when we see ourselves in the miserly version of Scrooge, to recognize how that miser was not always so cruel and heartless and how it was possible for even him to change, to defy the odds, and to overcome his own weaknesses and dark past. Scrooge was reborn as profoundly as any character in any story ever told. We can be similarly reborn, rejuvenated, and remade.

The darkness can pass from us as it did for Scrooge, leaving a bright and jovial morning. The regret can be replaced by forgiveness and second chances. The pain can be swallowed up by joy and love. The bad can be erased by the good.

Redemption can be ours as it was Scrooge’s. It can also come to us as quickly as it did for Scrooge, though we don’t have to be haunted by a procession of ghosts to grasp it. The Lord, whom Dickens described as the “mighty Founder” of Christmas, has made redemption available to each of us. Yes, redemption is available to every Scrooge in the world.

At the end of the day, the descriptions of Scrooge as a redeemed ought to inspire us. He became good, went about doing good, smiled, laughed, and loved life. He changed his heart as we all may. I conclude with a warm thanks to Charles Dickens for his inspiring tale, a word of praise to the Founder of Christmas, who is Christ the Lord, and a word of counsel from another inspired soul, Benjamin Franklin. Franklin knew what Scrooge discovered; namely, the secret to happiness. He said it in these words:

“Let no pleasure tempt thee, no profit allure thee, no ambition corrupt thee, no example sway thee, no persuasion move thee, to do anything which thou knowest to be evil; so thou shalt live jollily, for a good conscience is a continual Christmas.”

This Christmas, let “Humbug!” stay in the past and let redemption shine in your soul. Merry Christmas! And may God bless us, every one!

Zack Strong,

December 15, 2023

I enjoyed the read over coffee this morning. I had learned much from this story also. You can feel Christ entering in to guide and draw Ebenezer back to HIM and into the Light of HIS love. It is a wonderful story indeed and your shared thoughts were also an enjoyable read regarding it. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well done, Zack. It was heartwarming and thoughtful. I agree totally that we can, and all must change. We can allow our mistakes of the past to immobilize and embitter us with regret and sorrow or we can dump them at the feet of our Lord and Savior through repentance and start today to be who we can and should be. The choice is ours. Our challenges can harden us or make our hearts tender and meek. We all have this choice to make.

LikeLiked by 1 person