“Good Samaritan Law? I never heard of it. You don’t have to help anybody; That’s what this country’s all about. That’s deplorable. Unfathomable. Improbable.” – Jackie Chiles, Seinfeld

A city is not a community. A group of people living together is not a community. A cluster of houses in a common location is not a community. A political jurisdiction on a map is not a community. What, then, is a community?

I have lived in big cities with millions of inhabitants, medium-sized cities, tiny towns, and even remote villages. I have lived abroad in Russia and Panama and in many varied locations in the United States including Idaho, Washington, Arizona, Wyoming, Alaska, Utah, and Hawaii. In the rural villages and towns in several of these states, I learned the true meaning of “community.”

My first real introduction to “community” was when I lived in picturesque Port Lions, Alaska, as a teenager. When I lived there, the population was around 200. In the theme song of the popular 80s show Cheers, we hear the memorable line: “Sometimes you wanna go where everybody knows your name.” Port Lions is a place where “everybody knows your name” and you know theirs.

In Port Lions, not only did you know everyone’s name, but you could often identify who was driving past your house by the sound of their vehicle. You saw the same people at school, at the post office, on the five miles of unpaved roads, at the airstrip, at the harbor, at the dock, at the dump, on the ferry, and in the woods.

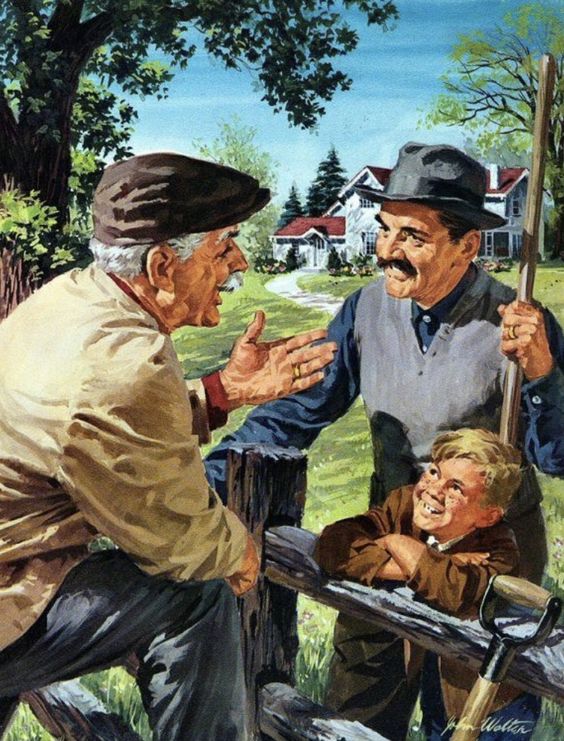

When you needed help, they were there. When you wanted to talk, they were there. When you wanted to throw a party, they were there. When you needed advice, they were there. When you were sick and needed a meal delivered to your house, they were there. When your car broke down and needed a hand, they were there. When your car went into the ditch, they were there. When school kids won in sports, they were there. When they lost in sports, they were there, too. They were always there.

George Washington gave what to me is the keenest definition of “friendship” I’ve ever heard. It applies to our discussion of “community.” Said he:

“Be courteous to all, but intimate with few, and let those few be well tried before you give them your confidence? True friendship is a plant of slow growth, and must undergo & withstand the shocks of adversity before it is entitled to the appellation” (George Washington to Bushrod Washington, January 15, 1783).

Communities are like true friends – they stick together through thick and thin, black and blue, rain and shine. In Port Lions, we stuck together and faced challenges as a unit. One small example helps to illustrate. Kodiak Island, where Port Lions is located, is home to one of the largest bears on the planet – the Kodiak brown bear. Problems with these bears were rare. In fact, it was common for people to go to the local landfill and watch bears lumber out of the woods, tear through trash, and drag whatever morsels they found back into the forest. Our version of a drive-in theater.

If the bears happened to enter the community, however, the phone lines lit up as everyone called everyone else to warn them and to make sure everyone was safe. Would this, or even could this, happen in a big city?

It was especially true that my family stuck together during our years in Port Lions. My family became more closely-knit than ever before. We started the day together at home. We then went to school together (my Dad is a teacher and my Mom began working as an aide when my youngest sibling began attending school). My Dad was my coach in the afternoon. My family saw each other in the evening for dinner, scripture study, relaxation time, etc. On Sundays, we also had Church in the home – all three hours of it each week. Nothing could have welded our family more closely together than living in Port Lions. For that fact alone, I consider Port Lions the best place I have ever lived and thank God with all my heart for the opportunity I had to live there.

In Idaho, which is my home state, I have lived thrice in towns of 600 people or fewer and will soon move to Idaho City which fits the same bill: Grandview; Bancroft; and Weippe. In the latter two specifically, the sense of community was alive and well.

I moved to Weippe in 2014 after having lived for several years in a medium-sized metro area. That particular metropolitan area in Utah is ranked as one of the safest in the nation and is a place where crazy things don’t generally happen. Even so, the difference was stark. No matter how safe or friendly a city is, it can never compare to the closeness and camaraderie you feel in a small community where everyone knows everyone else and associates with them in-person on a regular basis. That’s just not possible in a metro area of 300,000. Most of the people you meet daily will be complete strangers and, though nice they may be, you’ll feel no personal connection with them.

In Bancroft, Idaho, community spirit was also reality. Members of the biggest local church chopped wood for people to burn in the winters. We had a great event each year where we lit the Christmas lights, enjoyed food and live music, and welcomed Santa Claus with cheers. I loved my daily trips to the post office because I had the chance speak with the wonderful postal woman Pam. People knew your name and would greet you with a smile or wave at you on the road. You could even stop your car on the road and talk window-to-window with other drivers. You had the time – there were no traffic jams. The atmosphere was simply different.

Name a city anyone on earth where you can regularly enjoy the same benefits I’ve described. I don’t know one. I’ve never been in one. Yes, there may be individual neighborhoods within cities where everyone is close, everyone helps each other, and everyone associates regularly. However, I know of no city on earth where that same situation, closeness, friendliness, and intimacy prevail.

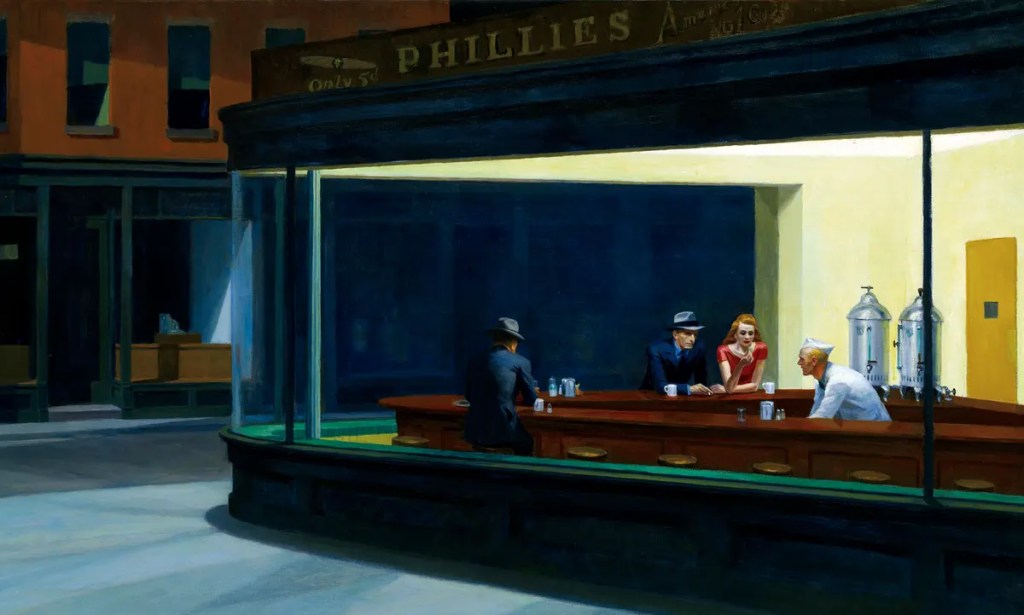

Instead, cities are toxic, both literally and figuratively. Cities are often polluted, dirty, trashy, rundown, full of litter, littered with homeless people and drugged-up wrecks of humanity, drab and dingy, industrial and cold, shapeless and bland, etc. There is greater division, cliquishness, anger, and stress; higher prices, more disease, more crime, and greater tragedies. True, I’m generalizing. Some cities have bright colors, nice sights, beautiful parks, etc. Some are also relatively happy or peaceful and don’t have much violent crime. But, as a generalization, cities are dreary, drab, cold, unfeeling, and more unsafe. We call them “concrete jungles” for a reason.

When you confront people about the toxicity of their city, however, they often recoil and get angry or defensive. Yet, if they’re honest, they will admit that large cities are not conducive to community, oneness, unity, intimacy, or geniality. Sinead Mulhern wrote an interesting op-ed about her experience with Toronto, Canada, compared with her experience in Cuenca, Ecuador. She wrote of arriving in Cuenca and being invited to a party, saying:

“I’d arrived in Cuenca two months before, and this was just the latest example of the city’s friendliness—a stark contrast to the life I’d left behind in Toronto. Here, hellos didn’t come with an arm’s-length handshake but rather with a hug and a kiss on the cheek. Strangers always asked me about myself. Neighbours offered rides in their cars. My landlady never failed to ask about my afternoon run. When I left Toronto after living there for eight years, I wasn’t sure what I was looking for. But here was the answer: community.

“That’s something I didn’t have at home—and, it turns out, I wasn’t the only one. Scientists and world leaders are starting to refer to a loneliness “epidemic.” The New York Times reports that about half of Americans reported feeling lonely—and 13 percent say no one in their life knows them well. And in the U.K., the problem was bad enough that then-Prime Minister Theresa May appointed the world’s first Minister for Loneliness in January 2018. Here at home, 28 percent of Canadians now live alone, which is the highest number on record and a risk factor for loneliness.

“All of this social isolation can have a real impact on our health. A 2015 study out of Brigham Young University found loneliness was as big a risk factor for early death as smoking 15 cigarettes a day, making it a bigger health risk than obesity and a sedentary lifestyle. And, according to the U.S. National Institute on Aging, research has linked social isolation to other ailments, like high blood pressure, heart disease, anxiety, depression and even Alzheimer’s disease.

“When I lived in Toronto, I never realized how lonely I was. I’d moved to the city for school and stayed after I graduated, but as the friends I’d made moved away, I was left with a gaping hole that I tried, unsuccessfully, to fill. I swiped right and became familiar with the communication cop-out that is ghosting. I went to parties with seemingly impenetrable Toronto cliques and felt like a permanent fringe friend. I did have meaningful friendships, but in my experience, Toronto is a place where community ranks lower than one’s job, relationship and personal commitments.”

I’ve spoken with many people who have expressed nearly identical views and experiences. They feel, on a gut level, that someone isn’t right about cities. It’s not how humans are supposed to live. We’re not supposed to be nameless faces in a crowd; a cog in a giant machine. Rather, we’re supposed to be unique individuals in a community of individuals working voluntarily together for their collective good and the betterment of the whole. While perhaps not impossible to achieve in cities, it is nearly so.

Cities simultaneously promote collectivism and extreme individualism. I’ve always been a supporter of individualism. However, there are limits. Thomas Jefferson referred to “rightful liberty,” for instance, and said that “rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will, within the limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others. I do not add ‘within the limits of the law’; because law is often but the tyrant’s will, and always so when it violates the right of an individual” (Thomas Jefferson to Isaac H. Tiffany, April 4, 1819).

Individual rights, agency, and accountability are paramount; yet they must be circumscribed by the rights of other people and the general welfare of the community. This is not collectivism, but rightful individualism. Collectivism says that the community is more important than the individual and it does the very thing Jefferson warned about but in reverse – it restricts rightful Liberty and violates the rights of individuals to promote an undefinable mass called “community.”

Collectivism is not “community” in the sense I’m using the term today. It is an aberration of my idea. My idea of community is a unit, team, or group of people who harmoniously exercise their individual rights to promote a better life for everyone. No one steps on anyone’s toes. No one elevates themselves at the expense of others. No group has legal advantage over another. All are on the same level and enjoy the same rights, but willingly and voluntarily use their personal agency to assist others, work with them, and form a stronger unit.

It’s impossible to read the holy scriptures without encountering the Son of God saying that we should be “one.” He was not a Marxist. He was not a collectivist. Yet, He desired us to be one in spirit, in ideals, in willingness to help, in purpose, in mission, in compassion, and in every other good and wholesome way. He never envisioned us to be “one” mass of humanity with no individualism. Rather, His Gospel speaks of individuals being rewarded, or punished, for their own individual acts. He told parables of individuals using their unique gifts and talents wisely to expand what He gave them and to do the most good possible for others.

Community, really, is about connections. It’s connecting with other people. It’s becoming one with them, not in substance but in purpose, ideals, and goals. Early Americans had many divisions, but their goals and principles were nearly identical. They merely squabbled about how best to implement their shared vision. Having a shared vision that individuals join up with others to reach is what makes a community.

Merriam-Webster’s dictionary gives many definitions of “community,” but its basic definition states that a community is “a unified body of individuals.” I believe this is apt. Like in Port Lions, Weippe, or Bancroft, a community is not merely a political or geographical jurisdiction, but a group of people voluntarily uniting in the spirit of unity and shared interest. They don’t have to help each other, but they do. They don’t have to come together for events and service projects, but they do. They don’t have to support the local sports teams and schools and churches, but they do. They don’t have to help others move into or out of the town and shower them with food and support in hard times, but they do.

In cities, we become faceless, unnamed parts of a faceless, unnamed mass; proudly trumpeting our individuality while actually lacking both individuality and the connections with others that make a true “community.” We effectively disappear. We become consumed in the mass of humanity from whom we are paradoxically disconnected.

In cities, we may have certain connections, friends, and acquaintances, but rarely do we connect with passersby and strangers. Our primary interactions with other human beings are with strangers who don’t know us, who don’t want to know us, and who won’t be there for you when things get tough; nor will you be there for them when they need support.

We may have our own small “communities” within the larger population, but our cities lack community spirit and oneness and don’t operate as cohesive units. Each of these tribal “communities” wars against the other in a competitive manner, cementing divisions and buildings walls where there should be bridges.

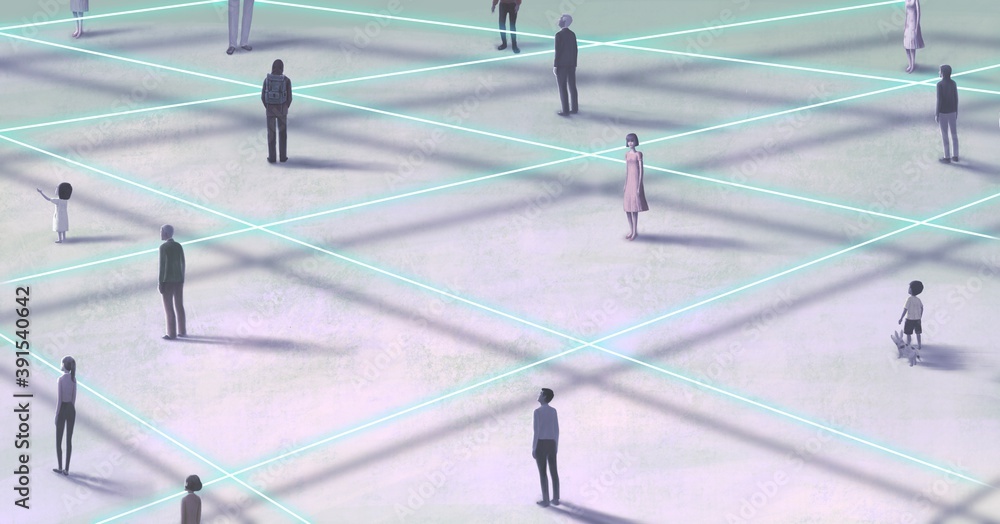

This depressing disconnectedness and tribalistic divisiveness have only been exasperated over the past several years as a result of insane COVID tyranny. “Social distancing,” which is medically unsound advice, inflamed loneliness, depression, mental illness, bitterness, anger, self-isolation, and other feelings that don’t benefit or better communities, let alone individuals. Jack Langley at America’s Future published an article talking about the negative changes that have swept the globe in the wake Coronahoax tyranny. He wrote:

“It is inherent to human nature, and particularly to American culture, that we feel the need to be a part of something bigger than ourselves and experience. Whether that be a college, a social club, a religious institution, or even a prominent activist group. We innately feel called to be a part of something, a community of like-minded people if you will. But are we capable of feeling a part of any community if we are only interacting online? I would say it’s possible, but that it is not sustainable long term.

“Life itself is a collection of human experiences. We experience the first day of primary school as a small child, nervous and excited to finally begin education with peers. We experience the first day of college or our career, most often with an independent streak desiring greatly to find out what it is you plan on doing in the world. We innately have the desire to travel to physically experience other places, cultures, and their communities. I would argue that a collection of human experiences tied together thinly through a computer interface leaves much to be desired.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has caused the majority of Americans and quite possibly the world, to forget the importance of community. And this could really be a problem down the road. Communities are what fight back against the onslaught of problems that life hands us . . . We know that as Americans we can deal with anything as a unified group, working together.

“Unfortunately, the self-isolation caused by a global pandemic has caused the country to effectively lose its sense of community because we are simply not engaged with each other as much as we used to be. Life is terribly difficult for even the most clever of people, but is much more manageable, and far more enjoyable, if we do it with a community we trust, cherish, and genuinely enjoy being around. A sense of community is as important to the foundation of the United States as the Constitution itself.”

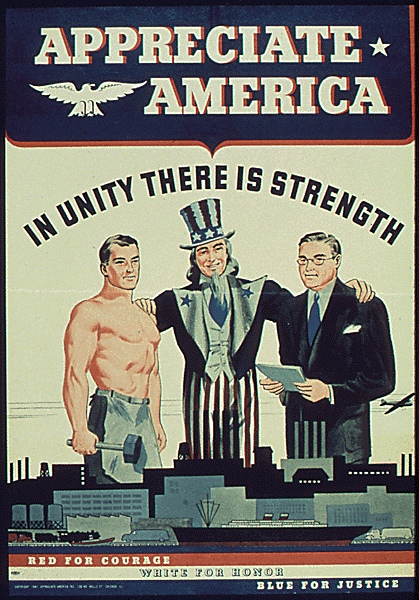

Who can disagree that having fierce community spirit was crucial in Americans achieving Independence? It was so important to our People that we named our great confederacy the UNITED States. We emphasized our oneness – our shared principles, vision, and mission as an “empire of Liberty” and a refuge for the oppressed of mankind. We enshrined rights such as the Freedom of assembly, worship, speech, and the press in our founding documents because we respected all individuals in the community and wanted each one to feel like a contributing, full member of the whole.

America was not founded as a collective mass where the majority rules and half the community doesn’t matter. We were, rather, founded as a Republic where individual states, made up of individual communities with individuals working together within them and holding equal power, came together for collective goals and to forge something great. Some of those goals were written into the Preamble to the Constitution:

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Individuals came together in a united capacity to defend themselves, ensure their rights, perpetuate peace and the general welfare, and to enjoy the blessings of Liberty. Is not this community? It is a community of shared ideals. It is a community of principles. It is a community of individuals voluntarily linked together to do unitedly what they could not do alone. Unless America remembers her heritage, she will eventually fall.

In a broader sense, unless people remember and reestablish the virtues of community, they will continue to grow apart, breed division, and devolve into disarray and tribalism. In a letter not long before his death, the percipient Thomas Jefferson gave this profound counsel:

“adore God. reverence and cherish your parents. love your neighbor as yourself, and your country more than yourself. be just. be true. murmur not at the ways of Providence” (Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Jefferson Smith, February 21, 1825).

Do we love our country more than ourselves? Do we value the community and seek to better it? Many, it seems, don’t give a hoot in hell for their country or community. They live only for themselves. In so doing, they tarnish the reputation of our republican system of individualism. People abroad often look in at the United States, see our recklessly selfish behavior, and create a perception in their heads of something that America is not.

Through my job teaching English, I have spoken with many people from Latin America who have erroneous perceptions about us. Recently, a man from Mexico asked me my opinion about my reception in Latin America versus how I’m treated in America. He was of the opinion that Latin American peoples are more open and welcoming. He thought I would readily agree. I told him that, actually, in my lifetime, I’ve experienced far more of a welcoming attitude and community spirit – true friendship, concern, and service – in the United States than in Latin America.

My friend was surprised at my response. I explained that America is seriously divided and that what is true about one part of it is not true about other parts. My part of America – rural America – is community-oriented, friendly, open, helpful, hard-working, close-knit, and kind. However, my friend was thinking of New York City and the big metropolises he sees on the news. To him, that is America. To me, that is a sad divergence from traditional American culture, spirit, and norms.

Many see America as something to exploit for their own ends; a cash cow to milk. They view things much like fictitious attorney Jackie Chiles from the hit sitcom Seinfeld. His bombastic character said: “Good Samaritan Law? I never heard of it. You don’t have to help anybody; That’s what this country’s all about. That’s deplorable. Unfathomable. Improbable.”

What’s deplorable, unfathomable, and improbable is the fact Americans have fractured their communities, divided their strength, and turned inward against each other at a time when unity is needed. We should be one nation under God, one nation united in the principles of Liberty, one nation behind the Constitution and rule of law, one nation opposed to communist barbarity, and one nation standing for Christian morality.

To restore our former station, we must rekindle the glorious bonds of community. We must keep alive the community spirit; the American community spirit. We can’t afford to become disunited and divided any more. Everyone knows that “divide and conquer” is the classic strategy to topple empires, groups, families, marriages, and friendships. At the end of the day, that nation is strongest that, while not sacrificing individual Liberty, initiative, and stewardship, is united in one in principles of goodness, service, truth, light, and community.

Zack Strong,

June 21, 2023

I would love to live in a community.

My small city has been destroyed by drugs and crime..

The only thing that keeps me from packing up to go join the Amish, is I would miss my close-knit family.

LikeLike